Singapore's GRC system likely advantages the PAP: a game-theoretic analysis

Tue Jul 07 2020tags: exploration political science game theory public

(with huge thanks to Tsun Lok, Bassel and Chin Wee, and thanks to all who proofread early drafts and gave helpful comments).

~2000 words

Overview

I develop a game-theoretic model of electoral contestation in Singapore and show that having multi-member GRCs rather than only single-member constituencies (SMCs) gives the incumbent party more seats if the incumbent's "strong" candidates are significantly stronger than the opposition's ones.

Given that this assumption is likely to be true, this suggests that the GRC system advantages the PAP and gives it more seats than it would otherwise win under a "pure" single-member constituency system like the UK's.

Background

First---what's a GRC? From the Wikipedia page:

A Group Representation Constituency (GRC) is a type of electoral constituency (unique to Singaporean politics. They are multi-member constituencies (usually 4, 5 or 6 seats) which are contested by teams of candidates from one party or from independents.

In each GRC, at least one candidate in the slate must be from a minority race (ergo non-Chinese). The ostensible purpose of the GRC system is to ensure minority representation. It may well do that, but might it inadvertently benefit the PAP as well?

GRCs operate with a plurality voting system voting by party slate, meaning that the party with the largest share of votes wins all the seats in the GRCs. But this may make us ponder. A strong candidate can single-handedly win all the seats in the GRC. For instance, if the PAP fielded four chimpanzees and the late MM Lee in a five-member GRC, it would handily win that GRC (and thus five seats) through the force of MM Lee alone. In contrast, an electoral system that only contained single-member constituencies (SMCs) would mean that MM Lee could only ever win one seat by himself no matter how great he was.

The reasoning I've put forth is quite intuitive: strong MPs can "carry" weak ones in the GRC system but not the SMC system. But how do we formalise this intuition? And how large is this effect, if any? I come up with a toy game-theoretic model to answer these questions. I show not only that the GRC system gives the PAP an advantage, but also the extent of this advantage---and that that this advantage works through magnifying existing advantages that the PAP already has.

Building a game-theoretic model

First a preliminary note. When modeling it is vitally important to make the model as simple as possible---and then even simpler than that. Otherwise the problem becomes completely intractable. And thus this model leaves out many important considerations by necessity.

With that said: In any election there are stronger candidates and weaker candidates. For simplicity, let us consider two types of candidates: (1) eloquent, long-serving, well-respected candidates (minister-calibre candidates) and (2) other candidates (perhaps-currently-not-minister-calibre candidates). For example in Jurong GRC, one might think that Tharman and Xie Yao Quan would respectively exemplify the qualities of each category.

Let's now assume that a "weak" candidate has a strength of 0 and a "strong" candidate a strength of 1. Let's further assume the PAP's stronger candidates are stronger than the Opposition's candidates. This can be thought of as an "incumbency bonus" and you can interpret it in any way you find reasonable. I am partial to three main explanations for this incumbency bonus:

Firstly, the PAP's political dominance may give it a recruiting advantage (as minister-calibre candidates may not want to risk their careers on joining Opposition).

Secondly, the PAP's political longevity gives it an incumbency advantage. If two candidates are identical but one has been a minister for ten years and the other an Opposition MP for five, the former will be perceived as stronger by the electorate.

Lastly, the relative friendliness of state media to the PAP's interests can also give its candidates an incumbency advantage. Whichever explanation you prefer, let's say that "strong" PAP candidates have strength 2 but "strong" Opposition candidates only 1.

Now consider this game.

The 2020 General Elections has 14 SMCs, 6 four-member GRCs, and 11 five-member GRCs, for a total of 93 (14 + 6 * 4 + 11 * 5) seats. This is a total of 31 districts. Each party wants to find the optimal assignment of strong and weak candidates over all 31 districts such that:

- in each district, the party that has allocated the higher sum of candidates' strength will win all the seats in that district;

- both parties seek to maximise the total number of seats they expect to win.

(those with a background in game theory may recognise this as a variant of the Blotto game).

This can be a bit confusing, so let's run through a tiny example. Let's suppose that there are only two districts: Yuhua SMC and Jurong GRC. Let's further suppose that the PAP has two strong candidates (Grace Fu & Tharman) while the opposition only has one. If the PAP chooses to field one strong candidate in each district, its strength in each district is:

- Yuhua SMC: 2

- Jurong GRC: 2

But if it chooses to field both strong candidates in Jurong GRC, its strength in each district is:

- Yuhua SMC: 0

- Jurong GRC: 4

Now suppose the opposition chooses to field its strong candidate in Yuhua SMC. Its strength in each district is therefore:

- Yuhua SMC: 1

- Jurong GRC: 0

Then if PAP had chosen to field one strong candidate in each district it wins all six seats, because it wins Yuhua SMC (2 > 1). But if it chose to field both strong candidates in Jurong GRC it would win only 5 seats as Yuhua SMC would be lost to the Opposition.

Hopefully that clarifies.

One final point: this game can be played either simultaneously or sequentially. In the simultaneous version of the game, both parties choose where to send their MPs at the same time with no idea what the other party is doing. In the sequential version of the game, the PAP first chooses how to field its candidates. Then the Opposition observes the PAP's move and then chooses how to field its candidates. The rationale for this is that the opposition has some idea of which incumbent PAP MPs are in which area, and whether they are strong or not.

In this exploration I use the sequential game as it is (1) easier to solve and (2) I suspect that the results will be even more skewed in favour of the PAP if the Opposition has no last-mover advantage (see Technical Appendix). That is to say, if we find a PAP advantage when the Opp gets to observe the PAP's actions, we should strongly suspect that this advantage will increase when the Opp doesn't get to observe the PAP's actions.

So that's the game-theoretic model. To reiterate:

- Each party is endowed with a different number of strong and weak candidates. The PAP's strong candidates are worth 2 while the Opposition's candidates are worth 1.

- First, the PAP assigns strong and weak candidates to all 31 districts.

- After having observed the PAP's assignment, the Opposition assigns their strong and weak candidates to those 31 districts.

- We compare the strength of each party in each district and add up the expected number of seats won by every party (Draws give half the seats of the district to both parties).

We've just specified the game, and can now analyse it.

Methodology

The full electoral situation has 31 districts and 93 seats---too large to analyse quickly---so I decided to shrink it by one-third to make it tractable. In my reduced game, there are six SMCs and five 5-man GRCs, for a total of 31 (6 * 1 + 5 * 5) seats. I made sure to keep the ratio of SMC and GRC seats roughly similar to the full electoral case.

We need one more piece of information to solve the game: the number of strong and weak candidates that the PAP and Opposition have. You could attempt to use your judgment to identify this number, but this would introduce human bias; instead, I try a variety of different combinations to make sure my results are robust.

I didn't try to do anything fancy when solving the game: I just used a brute force approach. A sequential game with perfect information can be solved with backward induction. Here's how I went about it:

I first generated exhaustively all possible ways the PAP could assign candidates to districts. I then did the same for the Opposition.

Then, for each of these PAP-assignments, I looked at each of the Opposition's assignments and selected the Opposition's optimal strategy: that is, I found the Opp-assignment that would give the most seats given that PAP assignment.

This told me what the Opposition's best response/optimal strategy would be given each PAP assignment.

Finally, I looked at all the PAP-assignments and Opp-best-responses, and chose the assignment that maximised the PAP's number of seats.

All this was done with Python in a Jupyter Notebook and can be found here (warning: very rough).

Results

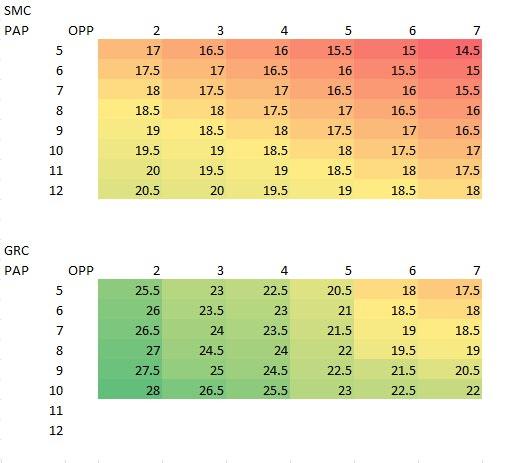

Including GRCs gives the PAP more seats compared to a pure-SMC electoral landscape. Figure 1 plots the number of seats the PAP wins under both types of electoral systems with different combinations of strong candidates.

The first table shows the number of seats won under the pure-SMC electoral landscape (i.e. 31 SMCs). For instance, the top left hand corner shows how many seats the PAP would win if it had five strong candidates and the opposition had two. The PAP puts its five strong candidates anywhere and the Opp judiciously avoids those strong candidates. The end result is that the PAP wins five districts, loses two districts, and draws the remaining (31-5-2 = 24) districts, winning a total of (24/2 + 5 = 17) seats out of 31.

The second table shows the number of seats won under a landscape with 6 SMCs and 5 GRCs. Again, let's look at the top left hand corner as an example. The PAP's optimal strategy is to put one strong candidate in each GRC (thus each GRC has strength 2). The Opposition chooses to put both strong candidates in one of the GRCs to contest it, causing a draw. The PAP thus wins half of the six SMCs, four GRCs, and half of the final contested GRC, for a total of (6/2 + 4 * 5 + 5/2 = 25.5) seats.

While in this case the PAP has more strong MPs than the Opposition, we can see that the PAP benefits under the GRC system regardless of the number of strong candidates. In fact, the PAP wins more seats (17.5 vs 14.5) even when it has a numerical advantage (5 strong PAP vs 7 strong Opp). The advantage is magnified when there is a large discrepancy between the number of strong candidates each party has.

Caveats

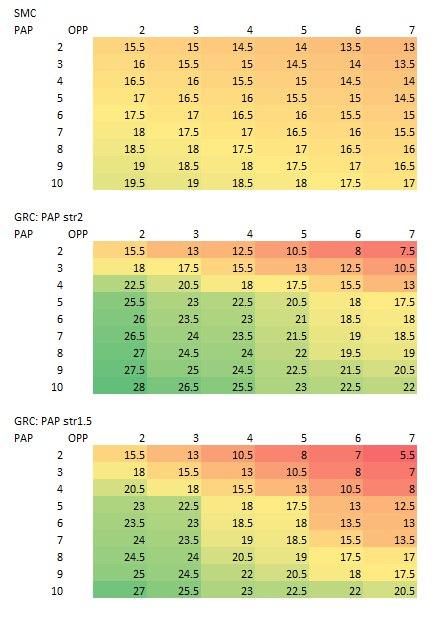

Firstly, my results depend strongly on the incumbency strength bonus and the relative ratio of strong MPs for each party. Here each strong PAP candidate is worth two opposition ones. With a low enough incumbency strength bonus, the last-mover advantage the Opposition has can give them the advantage.

Figure 2 shows the results of subsequent analyses I ran with a lower incumbency strength bonus (1.5 vs 2) and a larger range of strong PAP candidates. We can see that the GRC may actually disadvantage the PAP if the number of strong PAP candidates is significantly lower than the number of strong Opposition candidates. It's more accurate to think of the GRC system as a "variance-increasing" system.

However, I don't think looking at the lower end is that interesting, because (1) it seems unlikely that the PAP has significantly fewer strong candidates than the opposition, and (2) I strongly suspect that the PAP disadvantage will disappear completely in the simultaneous game without the WP's last-mover advantage.

Secondly, the results may be specific to a particular range of strong/weak MPs or a particular makeup of SMCs and GRCs. I've tried to ward this criticism off by trying multiple combinations but may have missed something. Nonetheless, I'm quite sure---but not 100% certain---that this analysis will hold for the larger 93-seat game.

Finally---to be clear, there is nothing inherent about the GRC system that benefits the PAP. It is only when paired with the assumption of incumbency advantage (and a reasonable number of strong v. weak candidates) that the GRC system becomes structurally favourable for the PAP. This insight is important, because it allows us to infer whether or not the PAP intentionally benefits from the GRC system. If it is, then we should expect to observe either a decrease in GRC size or an increase in the number of SMCs relative to GRCs in the future if the Opposition gains in relative size and strength.

Conclusion and discussion

Provided that the incumbency strength bonus is high enough, the GRC system advantages the PAP by letting it win more seats than it would have under a traditional single-member system. We should thus carefully consider whether the purported benefits to minority representation outweigh the increased disproportionality that results.

Future research should try to solve the simultaneous version of this Blotto game, and try to find a relationship between the incumbency strength bonus and the number of extra seats won.

Technical appendix

Claim: The simultaneous Blotto game will always give the PAP more seats compared to the sequential Blotto game.

Proof: Is this actually true? TBD. (Ask Bassel for help).